Reframing Protein: From Commodity to Critical System

Protein is no longer just a commodity. It is a vital, interconnected system sitting at the crossroads of global nutrition, economic stability, and environmental sustainability. With demand projected to surge 70% by 2050, the way we produce, distribute, and consume protein must evolve.

This is a cross-sector issue with global implications. From aquaculture in Southeast Asia to cattle ranching in Latin America, protein production spans borders and economies. Demand is accelerating due to population growth, urbanization, rising incomes, and heightened nutritional needs, especially in developing regions. Seafood demand alone is expected to rise by 14% by 2030.

Yet this growth trajectory exposes deep vulnerabilities in the system.

Protein-Climate Relationship

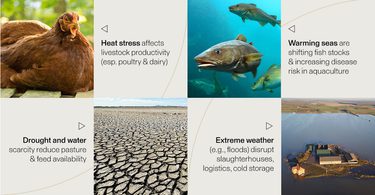

Protein production is highly climate-sensitive, relying on predictable weather, extensive cold chain logistics, and globalized feed supply chains. Rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and disrupted marine ecosystems are already impacting livestock productivity, feed crop yields, and fishery viability.

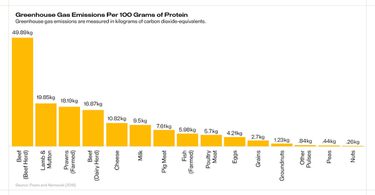

At the same time, protein is not only at risk from climate change but also a major contributor to it. Protein’s environmental footprint varies widely: beef production, for instance, generates nearly 50 kilograms of CO₂-equivalent emissions per 100 grams of protein, while plant-based proteins contribute less than one.

Supply Chain Issues

These pressures are compounded by structural fragility in the global protein supply chain. Over 20% of meat and seafood cross national borders. Trade disputes, disease outbreaks, and climate shocks like El Niño can rapidly destabilize markets. Examples include U.S.-China pork tariffs, African swine fever, and the Ukraine war’s impact on global grain prices.

Feed is a particularly overlooked but essential component. It accounts for up to 70% of livestock production costs, and the vast majority of global soy and one-third of grain production are used as animal feed. Heat, drought, and aquaculture’s dependence on finite wild fish stocks further compound the strain.

Cold chain infrastructure is another weak point. Essential for preserving perishable protein products, it is increasingly threatened by power outages, cyberattacks, and extreme weather. Many developing regions lack adequate cold storage, resulting in food spoilage and market access barriers. Meanwhile, rising energy costs — up 15 – 20% in some areas — threaten the affordability and resilience of cold logistics.

Industry Solutions

Despite these challenges, the industry is not standing still. Leading producers are proactively adopting solutions across genetics, feed optimization, regenerative practices, and resilient infrastructure. They’re also working to reduce emissions, improve animal health, and adapt to an increasingly volatile climate.

Innovation is key to closing the protein gap sustainably. Alternative proteins, while still less than 2% of the market, are gaining momentum. Cultivated meat and hybrid products, blending plant and animal proteins, offer practical paths forward. Feed innovations such as insect-based protein and algae, as well as precision nutrition, help to reduce reliance on traditional inputs. Smarter logistics and investments in cold chain efficiency can mitigate loss and stabilize supply.

To meet the growing global demand while navigating climate risk and supply chain fragility, we believe a future-fit protein system must be productive, resilient, and climate-compatible. We must stop thinking of protein as a standalone commodity and start treating it as a system in urgent need of redesign. Through efficiency, adaptation, and collaboration, we can reimagine the protein economy to secure food, profit, and planetary health for decades to come.

My colleague Matthew Walker and I will be diving deeper into this topic during an upcoming episode of the S2G Podcast. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Spotify and stay tuned.